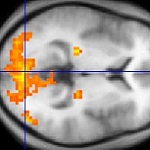

July saw the Congress of the International Union of Physiological Sciences taking place in the UK. Organised by the Physiological Society one of the recurrent themes was the growing importance of neuroimaging, both in medicine and other areas, including crime detection. In particular, there was an emphasis on the ethical issues involved and the need for society at large to understand the issues.

July saw the Congress of the International Union of Physiological Sciences taking place in the UK. Organised by the Physiological Society one of the recurrent themes was the growing importance of neuroimaging, both in medicine and other areas, including crime detection. In particular, there was an emphasis on the ethical issues involved and the need for society at large to understand the issues.

One paper, The promises and perils of brain imaging technology: an ethical perspective, presented by Dr Laura Cabrera of the University of Basel, brought the issue to the fore directly, while other papers discussed the medical applications and even commercial aspects.

One speaker was Prof Hank Greely of Stanford Law School. His emphasis was on the dangers of neuroimaging being exploited in ways that society at large is unaware of.

Prof Greely addressed areas where the techniques would have applications in the assessment and allocation of responsibility, particularly in relation to criminal behaviour. The process is already being used in lie detection and could be used, the professor warned, to ‘treat’ what he described as non-disease behaviours, such as criminal activity.

Following the conference he gave an interview to online newsletter Science Omega.

On the issue of the use of neuroimaging in lie detection he had this to say: “At least two companies in the United States are selling fMRI-based lie-detection services. In truth, more than 30 peer-reviewed articles have identified statistically significant correlations between particular patterns of brain activation and deception. That’s not bad; it’s better than the scientific data that we have for, say, fingerprints. Even so, I don’t think that this technology is ready to be used in a legal context.”

A related application with a possible legal context is the ability to determine whether someone is in pain, with the implications for personal injury cases. On that, Prof Greely was more confident.

“One of the most common complaints is back pain, which is quirky because it isn’t always accompanied by physical evidence. If we had an accurate way to identify individuals who are in genuine pain, we would be able to cut down on litigation and ensure a fairer distribution of money.”

An application of neuroimaging technology could lie in the area of marketing. Professor Gemma Calvert of the Nanyang Technological University in Singapore is also the founder of the world’s first neuromarketing consultancy.

In the introduction to her paper at the conference she wrote: “Companies…have conducted a substantial amount of research using the full gamut of neuroscientific approaches to understand, and ultimately predict, consumer behaviour with far more accuracy than has been permitted by reliance on spoken feedback.”

Whether we as a society want to see the techniques used in this way is a matter for the public to determine. What is needed, though, according to Professor Greely, is a more informed debate.

Picture by Washington Irving from Wikimedia Commons

“Speculate before you accumulate. I am a long term regular writer and advertiser in 'Your Expert Witness - the Solicitor’s Choice'. This investment pays me substantive dividends; I get more Expert Witness work with every issue. Not only solicitors and barristers but also judges seem to read it. It is a win-win situation. Success breeds success; I must continue to write and advertise.”

“Speculate before you accumulate. I am a long term regular writer and advertiser in 'Your Expert Witness - the Solicitor’s Choice'. This investment pays me substantive dividends; I get more Expert Witness work with every issue. Not only solicitors and barristers but also judges seem to read it. It is a win-win situation. Success breeds success; I must continue to write and advertise.”